Trusting our leaders

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

The closer we get to another round in the seemingly never-ending American election cycle, the more we begin to hear stepped up discussions about trust (or the lack of same) in our political leadership. Sadly, distrust in our elected officials is commonplace. But it is not just our politicians. A preponderance of high profile scandals has resulted in a dramatic loss of trust in our corporate heads and even in our religious leaders as well.

From the perspective of classical Jewish value teachings, nothing could be more untenable. The Talmud (Bava Batra 8b) makes it clear that no one can be appointed a communal leader unless he or she is completely trustworthy. Individuals “were not to exercise authority over the community, but that they were to be trusted.”

Where does trust come from? What are the factors that make for a trusting relationship between followers and leaders? What do you look for when it comes to trusting your own leaders – bosses, politicians, team captains, rabbis? Not surprisingly, many of the attributes we cherish in our own interpersonal relationships are the same traits we value in relationships with our leaders – honesty, reliability, constancy, and fairness, among others.

An analysis of Jewish texts on the subject makes it clear that in our tradition trust is the aggregate sum of a delicate combination of both competence and character. Whereas the general leadership literature is fond of distinguishing between leadership skills, those technical competencies a leader requires, and leadership attributes, those personal characteristics often thought to constitute the essence of good leadership, no such bifurcation exists in Judaism. In a formula made popular by Moses’ father-in-law, Jethro (Exodus 18:21), “You shall … seek out from among all the people capable men who fear God…,” effective leadership requires both competence and character. Only when both conditions obtain will followers trust their leaders. “It is not enough, taught Warren Bennis, Distinguished Professor of Business Administration at USC, “for a leader to do things right; he must do the right thing.”

While proficiencies, even those that can be globalized, may vary from position to position – and by the way, it is often a mistake to assume that competency in one area will necessarily translate into another arena – there are certain commonalities associated with character and integrity in leadership that are timeless. They are not unique to a particular leadership paradigm, and are, therefore, worthy of consideration by any who aspire to lead.

Of all of these, Judaism is particularly concerned with the connection between fiscal propriety and effective leadership. Traditional authorities, recognizing the opportunities and temptations often associated with high office, were especially vigilant about avoiding even the appearance of impropriety. Fastidiousness of the highest order was expected of communal leaders, even if their jobs went far beyond accounting and finance. The kohanim – Temple priests – for example, were proscribed from wearing certain bordered cloaks that could be used to illegally sequester coins, not because the priest were thought to be common criminals, but because their ability to lead required them to be above suspicion completely (Mishnah Shekalim 3:2). So too, the king was forbidden from sitting on the High Court (Sanhedrin) lest he be placed in the position of adjudicating certain issues that might benefit his personal finances (Sanhedrin 18b).

The medieval legalist, Moses Maimonides, set the bar particularly high for those involved in communal fundraising.

One should not contribute to a charity fund unless he knows that the one in charge of the collections is trustworthy and intelligent and knows how to manage properly, as in the case of Rabbi Hananiah ben Teradyon [who administered the communal charity funds so scrupulously that once when money of his own chanced to get mixed with the charity funds, he distributed the whole amount among the poor](Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Matanot Ani’im 9-10).

For Maimonides, involvement in the philanthropic sector, either as a professional or volunteer, demands impeccable fiscal ethics. Only when a community trusts its fundraisers, organizational executives, and lay leaders can it be expected to give generously. We can extrapolate from Maimonides’ teaching to the realm of business and politics as well. Investors and the general electorate need to know that those who seek their support – fiscal or otherwise – come not only with the necessary competencies to lead, but with the highest moral standards as well. Character is established not merely by mouthing the right words about financial accountability, but by a level of personal conduct, evinced in the actions of Rabbi Hananiah ben Teradyon that reflects a commitment to the highest level of integrity above all else.

Consider how different things might be if these were standards used to assess our contemporary leaders.

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

Playing in the big leagues

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

A recent 60 Minutes segment focused on the Giving Pledge, the commitment made by some of the world’s richest individuals to dedicate the majority of their wealth to philanthropy. In an extensive discussion that touched on issues ranging from strategic initiatives to measuring philanthropic impact, Charlie Rose asked whether this select group of billionaires ever discussed failure in the context of their charitable work. Warren Buffett seemed surprised by the question. With the avuncular candor his fans have come to appreciate, the Berkshire Hathaway chair gently chided his interviewer, “If you bat a thousand you’re playing in the little leagues.”

To state the obvious, effective leadership comes with the expectation of success. The leaders we admire most are those who accomplish their goals and who complete their missions. And yet one of the great ironies of leadership is that a willingness to experiment, to journey far beyond our comfort zones, and even to risk failure, are hallmarks of bold leadership. Buffett, of course, is completely right. If we play it safe all the time, remaining deeply ensconced in the ‘known,’ we can certainly appear to increase our success rates. But as every successful leader knows, there is no comfort in the growth zone, and certainly no growth in the comfort zone.

There are, of course, perfectly understandable reasons why many, particularly among those who lead charitable organizations, are excessively prudent when it comes to risk taking and bold decision-making. Leading institutions in today’s philanthropic environment often forces us to live in fear of alienating our funders. Wary that we will say or do the wrong thing, we opt for an abundance of caution. We prefer safe to courageous. We worship at the altar of consensus precisely because we are risk-averse. We cannot take the chance of trying and failing when donors want the assurance that their investments are guaranteed. Failure in this context is simply not an option. And so, to echo Buffett, we play in the little leagues.

But playing in the little leagues is for kids. In the history of the Jewish people nothing great ever happened without a willingness to step out on a limb, to take a chance and risk failure. ‘Safe’ for Abraham would have meant continuing in the pagan tradition of his father’s household. For the daughters of Zelophehad, not rocking the boat would have allowed prevailing practice to militate against their right of inheritance. For the prophets of Israel, consensus meant capitulating to the polytheistic practices of their day. And for the rabbinic sages, the path of least resistance was to surrender in the face of the Temple’s destruction. Playing in the “majors” involves risk, disruptive leadership, and more than a few mistakes. This was as true for the Maccabees as it is for today’s Women of the Wall.

The midrash (Numbers Rabbah) relates a well known story that when the Jewish people left Egypt they found themselves at the shores of the Red Sea paralyzed by argument as to which tribe would have the honor of crossing into the sea first. With the Egyptians in hot pursuit, only one man, Nahshon ben Aminadav, took it upon himself to risk both the wrath of his coreligionists and death by drowning (the ultimate failure). Undaunted, Nahshon waded into the waters all the way up to his neck. Then, and only then, according to the rabbinic sages, the waters of the sea split open allowing the Israelites to cross over and escape to safety.

The example of Nahshon makes it abundantly clear that bold decision-making – the kind of decision-making that has transformative powers – is incongruous with reticence and a fear of failure. If playing in the little leagues is good enough, then, perhaps, there is no need to worry about failing. But if the big leagues are the goal then taking risks and making mistakes come with the territory.

The Torah underscores the fact that notwithstanding the desire, even the expectation, of success, all leaders fail on occasion. Indeed, missions are often not accomplished. Consider Moses, the quintessential Jewish leader, who, despite myriad accomplishments, did not fulfill his life’s dream of leading the people into the Land of Israel. Who among us, however, would write off his exemplary career or dismiss his transformative leadership on that basis? The willingness to risk failure is a necessary precondition for great leadership.

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

Just a normal regular person?

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

At the height of the absurdist antics surrounding Toronto Mayor Rob Ford’s descent into infamy, a reporter inquired as to whether he considered his behavior appropriate for the mayor of a major North American city. Tellingly Ford responded, “I don’t look at myself as the mayor. I look at myself as a normal, regular person.” Reasonable people can certainly disagree as to whether Ford’s activities meet the standard of a “normal regular” person, but something much more significant lies beneath this attempted defense of the mayor’s actions.

To Ford being the leader of his city imposed upon him no particular obligations or behavioral standards. The idea, resonant in Jewish sources, that a leader is a dugma, a role model, was apparently anathema to him. One can certainly understand why. Even relative paragons of ethical virtue often resent the unwelcome scrutiny that accompanies leadership. Being a leader already involves a great deal of stress and responsibility. Superimposing an expectation of moral virtue seems unfair and onerous.

Yet without apology, in Judaism, leadership brings with it an expectation of heightened scrutiny and the expectation of an exemplary ethical standard. However unfairly, communal leaders must understand that their actions are placed under a microscope, precisely because they are leaders. The story is told of Aryeh Leib Sarahs (1730-1791), a hasid (disciple) of the great master, the Maggid of Mezhirech. Said Aryeh Leib famously, “I did not go to the maggid to learn Torah from him, but to watch him tie his boot laces.” In other words, justly or not, followers analyze even the most mundane and seemingly innocuous acts of a leader in order to extrapolate every possible nuance and lesson.

Burdensome as it surely is, to be a leader is to stand naked and vulnerable before one’s followers, a lesson the Toronto mayor never seemed to learn. The fact that leaders are held to a higher ethical standard than Rob Ford’s “normal regular” persons may seem unreasonable, but savvy leaders never forget they are always being observed. “Your employees are talking about you at the dinner table, listening to what you say, measuring how closely your words square with your deeds,” cautioned Craig Wasserman and Doug Katz in their 2011 book, The Invisible Spotlight.

When you are a leader others pay careful attention to even your smallest actions. This lesson was driven home to Anne Mulcahy when she became CEO of Xerox. Reflecting on her experiences in a 2010 interview with the Harvard Business Review, Mulcahy noted, “Everybody is looking at you. You can destroy someone by showing your emotions, particularly negative ones … If you come into the office looking like you’re having a very bad day, everyone reacts to your mood. As chief executive, you have to consciously set the right tone … CEOs have to manage those unintended displays, because of how much impact they have on other people.”

Mulcahy understood what so many great leaders have come to know. Notwithstanding Mayor Ford’s assertion to the contrary, leaders can never be “normal regular” people. By virtue of being leaders they carry additional responsibilities in all that they do. This message is powerfully illuminated in Moses Maimonides’ commentary on one of the Torah’s most controversial episodes. The Book of Numbers (27:12-18) describes God’s harsh decision to deny Moses entry into the Land of Israel. The text explains that this stems from an earlier episode in which Moses lost his temper in frustration and failed to follow divine instructions to the letter. It is difficult to read this account without feeling that Moses was punished unjustly. However mistaken his actions might have been, the severity of his fate seems excessive.

Yet, in his explication of the incident, Maimonides argues that, “God was strict with him … because they [the people] all modeled their actions upon his and studied his every word … Everything Moses said and did was scrutinized by them” (Shemoneh Perakim). Whether one finds Maimonides’ explanation satisfying or not, he understood something essential about effective leadership: no leader can expect to be just a regular person. This is true whether one is the mayor of a major city or the president of a synagogue, a communal professional or a corporate executive. If the expectation of excellence and the attendant scrutiny that accompanies leadership is unwelcome, one should give serious consideration to another endeavor.

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

Too powerful to feel your pain?

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

Recent evidence from the field of neuroscience sheds new light on the Torah’s teachings about power and empathy. A story featured on National Public Radio entitled, “When Power Goes To Your Head, It May Shut Out Your Heart,” describes research conducted by experts at Wilfrid Laurier University in Ontario, Canada on the ability of people to be empathic. Though the science is far more complicated than I am able to comprehend fully or evaluate critically, there appears to be evidence to suggest that empathy, that is the ability to put oneself in the place of another, is inversely related to the holding of power. To quote directly from the report, “Power fundamentally changes how the brain operates … feeling powerless boosted” people’s ability to empathize. And conversely “when people felt power, they … have more trouble getting inside another person’s head … power diminishes all varieties of empathy.” (npr.org)

The connection between powerlessness and empathy represents an underlying premise for much of the Torah’s ethical worldview. On four separate occasions, the Torah commands kindness to the stranger and each time the rationale for doing so is linked to the Israelite enslavement in Egypt. Consider but two examples:

- You shall not oppress a stranger, for you know the feelings of the stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of Egypt (Ex. 23:9).

- You must befriend the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt (Deut. 10:19).

It is significant that these injunctions appear in the narrative after the Israelites are freed from slavery; at precisely the time they might begin to exercise power of their own. According to the Torah’s calculus, powerlessness sensitizes us to the plights of others; it heightens our ability to feel compassion. The lack of power (i.e. slavery) is a humbling experience. And with humility comes a greater willingness to feel for those who also lack power (in this case, the stranger).

But as the scientific research has now established, the acquisition of power changes us. Powerful people have a difficult time relating to the needs and experiences of others. Sometimes the disconnection is based on economic factors. As power is frequently linked to affluence, individuals with money are often unable to put themselves in the position of those who struggle to make ends meet. This matter, however, is not limited to economics. Supervisors cannot relate to their direct reports. The famous and accomplished forget the challenges faced by ones just starting out. Individuals accustomed to getting their way find it difficult to understand the needs of others who strive to be taken seriously. The point is not that powerful people are evil, or that they lack a moral compass. But the acquisition and retention of power diminishes our ability to be empathic.

At its worst this means that people with power, as I suggested in a prior posting, are predisposed to abuse the perks that accompany their position. We who lead, therefore, are duty bound to reflect seriously upon ways in which we may be more susceptible to abusing our office than if we held a different post.

Reflection, however, while necessary, is hardly sufficient. The task at hand is to create systemic protections designed to assure that such abuses are mitigated. If empathy is a natural casualty of power, then those in power must be taught to compensate for their own proclivities. According to a social psychologist at UC Berkeley, Dacher Keltner, who studied the findings from Wilfrid Laurier, this can, in fact, be done. An emerging field of research, he says, suggests that, “powerful people who begin to forget their subordinates can be coached back to their compassionate selves.”

The Torah’s approach to this issue is instructive. The book of Deuteronomy imposes a series of restrictions on the king, including the number of wives he may have and the amount of gold and silver he is eligible to amass. This section of the Torah concludes with the following, “When he is seated on his royal throne, he shall have a copy of this teaching (Torah) written for him … Let it remain with him and let him read in it all his life … Thus he will not act haughtily toward his fellows… (Deut. 17:18-20).” The text recognizes that at the apogee of power the king is least likely to be empathic. For this reason, it requires him to self-correct and to engage in behavior (“read in it daily”) designed specifically to facilitate an increased sense of compassion and understanding.

The importance of this new neuroscience research is that it affirms what ethicists have long believed to be true. Now that this link between power and low levels of empathy has been documented, each of us who holds power, whether in the office, in our communal organizations, or elsewhere must work hard to pursue appropriate counterbalances.

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

Understanding the perks of power

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

Despite the ebbs and flows of the news cycle, Americans can be reasonably certain that scandals involving the inappropriate behavior of high-profile individuals are here to stay. The reality is that despite their often sexually charged salacious nature, these episodes have less to do with lasciviousness and more do to with abuse of power. Prurient as they appear on the surface, starring as they do an assortment of politicos, corporate executives, sports heroes, and religious officiants, they should not be dismissed as the work of sexually deviant outliers, but need to be understood instead as the result of unchecked leadership, something much closer to home for many of us. Indeed, I would suggest that lubricity aside, defining them solely as shameful sex scandals, misses the point.

Jewish sources have long understood a basic truth; positions of leadership bring with them an increased risk of abusing power. This does not mean that those who aspire to leadership are evil by nature, or that every leader is necessarily an Anthony Weiner, Lynndie England, or Brett Favre, in waiting. But the holding of power – whether as a department head or governor, a soldier or performance icon, a classroom teacher or a clergyperson – increases the likelihood of abusing that power. And clearly, as Lord Acton famously pointed out, the more power, the greater the chances for abuse.

According to the Bible, when the Israelites asked Samuel about establishing a Jewish monarchy, he pulled no punches in detailing the consequences: “This will be the practice of the king … He will take your sons … for his chariots. He will take your daughters as perfumers, cooks, and bakers. He will seize your choice fields, vineyards, and olive groves … He will take a tenth part of your grain and vintage … He will take your male and female slaves … He will take a tenth part of your flocks, and you shall become his slaves …” (I Samuel 8). In a nutshell, leadership brings with it the increased likelihood of mistreating others.

Perhaps the classic case in point is the tale of David and Bathsheba, history’s most arrant example of abuse of power. (If it’s been a while, spend a few minutes rereading the story – II Samuel 11:1-12:7.) As an individual David was a man of considerable accomplishment. He was bold and courageous, and a deeply sensitive human being as well; a poet, who purportedly authored 150 psalms. But, as a leader, David thought nothing of taking advantage of his power. He misused his privileged position to pursue personal ends, convinced that he could manipulate circumstances and control resources and outcomes in order to get away with the most deplorable behavior. Like many leaders, David believed that society’s rules simply did not apply to him.

David, however, was neither amoral nor antisocial. His actions, while despicable, must be understood as a function of his leadership, not of psychopathy or sexual deviance. Indeed, when the prophet Nathan confronted him with a parable about a rich man’s unjust treatment of an impoverished neighbor, David was appropriately appalled. He lacked neither a moral compass nor a conscience. As a leader, however, he was unable to get out of his own way; his proclivity for abuse stemmed from the very power he wielded.

Many will recall a more contemporary example of this link between leadership and abuse of power drawn from the case of President Bill Clinton. In his 2004 interview with Dan Rather on 60 Minutes, Clinton was asked how he might explain his behavior during the infamous Lewinsky scandal. The former President responded with the now infamous words, “… just because I could.” Like scores of powerful leaders before and since, Clinton was not unaware of his transgression, nor did he aver that his behavior was somehow ethically acceptable. Indeed, he characterized his actions as “morally indefensible.” Mr. Clinton’s problem was not about sexuality, but about the abuse of power that accompanies leadership.

Exploitations that manifest in inappropriate sexual activity often grab headlines and titillate the curious. But they are far from the only examples of leadership dysfunction. Anyone who has ever signed a paycheck, written a reference, approved a vacation, diagnosed a patient or counseled a parishioner runs the risk of abusing power. Representatives of the military and the police, professors, youth leaders, parents, even celebrities, anyone who holds power or who is perceived as holding power has an increased likelihood of misusing the very leadership that defines them. As Jeffrey Pfeffer, Professor of Organizational Behavior at Stanford University wrote in the Harvard Business Review (July-August 2010), “Whenever you have control over resources important to others – things like money and information…” you have power. And with power comes the increased likelihood of abuse.

To contravene such proclivities classical Jewish teachings call for systemic controls designed to counterbalance the risks of abuse inherent in leadership. The Torah’s restraints on the monarch, for example, stand out as an unapologetic attempt to circumscribe the power often associated with executive privilege. “He shall not keep many horses or send people back to Egypt to add to his horses … And he shall not have many wives … nor shall he amass silver and gold to excess. When he is seated on his royal throne, he shall have a copy of this Teaching (torah) … Let it remain with him and let him read in it all his life … Thus he will not act haughtily toward his fellows …” (Deut. 17:16-20).

The Torah’s pragmatism in this regard is significant. Rather than impose an unrealistic standard on leadership, an idyllic paradigm of perfection, the text begins with an assumption that the risk of abuse is endemic to the holding of power. The goal then is to contain its nefarious impact not to alter human nature.

The Deuteronomic limitations on leaders assume an enhanced resonance in light of an unprecedented study conducted by former University of Kentucky psychiatry professor Arnold Ludwig. Over a period of eighteen years Ludwig studied more than 1900 twentieth-century political leaders. He uncovered a number of striking links between human rulers and alpha male primates. Common to both is what he calls the “Perks of Power,” tangible benefits that accrue to the ruler (simian and human), simply by virtue of being the leader. These include: increased sexual access (which in humans results in more extramarital affairs and polygamous relationships), more offspring, greater access to resources, and increased deference and respect from followers (Arnold Ludwig, King of the Mountain: The Nature of Political Leadership). Ludwig’s analysis is focused on political leaders but the evidence clearly suggests that similar conditions obtain in the corporate arena, the military, as well as sports and entertainment, among several other sectors.

When the Torah’s strictures are refracted through the lens of Ludwig’s research, the conclusions are striking. Leadership has its privileges and those privileges often include wealth and access. Left unchecked they lead to exploitation, abuse, and misconduct. Precisely because leadership is a condition precedent to abuse, protective measures are required. In proscribing sexual and economic excesses (the very same areas that Ludwig found to be most prone to abuse by leaders), and by insisting that the leader avoid haughtiness, specifically the flaunting of privilege over those (s)he is expected to serve, the Torah both acknowledges that abuse is inherent in the leadership process and affirms that such abuse can be palliated, that is, relieved without ever being fully cured.

Yet, as the case of King David makes clear, even divinely mandated restrictions on leadership often prove ineffective at curbing the abuse that comes with human power. For this reason, Jewish communities have historically organized in ways designed to forestall such excesses. Referred to in the Talmud and subsequent Jewish sources as the system of ketarim (crowns), power is divided across a tripartite framework of religious, educational and political leaders. By circumscribing authority and insisting that no single leadership type (keter) can amass too much power, the “ketaric” system seeks to attenuate abuses associated with leadership and its perquisites.

It would be naïve to suppose that either legislation or systemic stricture can eliminate the risk of abuse. And, as recent high profile examples have made painfully clear, Judaism’s insights into these matters have not prevented Jews from being among the most egregious offenders. But there is much to be learned from classical Jewish teachings on leadership ethics that might contribute, however modestly, to the tikkun (repair) so desperately needed. The most effective place to begin is so obvious it is often overlooked – the training organizational leaders receive throughout their careers.

The highly regarded statistician, Nate Silver is fond of pointing out that when it comes to prognostication, the very awareness of a particular proclivity is an important first step in overcoming associated biases. The same might be said of leaders, from politicos to clergy, from CEOs to first responders. To avoid the untoward excesses frequently found among leaders one must first be sensitized to the fact that exercising power brings with it an increased likelihood of abuse. This is not just true for some, it is true for all. Abuse is not the province of a deviant few. It is a risk that must be recognized by everyone who holds power. No long-term solution is possible absent such an acknowledgment ab initio.

The training and development of leaders is a multi-billion dollar industry today. It includes everything from graduate degree programs to industrially-based leadership institutes, from executive MBA’s to highly exclusive, by invitation only think tanks. Organizations, public and private, large and small, provide training for their leaders. Google estimates more than 397,000 separate entries under the heading of “leadership training” alone. It will hardly be surprising to know that only a fraction of these give serious treatment to leadership ethics in general, and to the issues associated with the use and abuse of power in particular. Sadly this is true not only in the corporate and for-profit arenas, but in the social sector, including the Jewish community, as well. Rarely, if ever do programs purporting to be about leadership training ever discuss the risks of power abuse in leadership. Rarer still are programs of Jewish leadership that help those who hold power to recognize that even when they are unaware of doing so they may be taking advantage of their positions.

Rabbi Tarfon in the mishna of Avot (2:16) cautions that while ours is not to finish the job, we are not free to desist from trying either. While the abuse of power is bigger than any single member of the Jewish community, many of us are in positions to insist that leadership-training programs deal with this issue head on. Doing so would be an important first step.

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

—(Portions of this posting were published previously in eJewishPhilanthropy.)

Learning leadership at Wimbledon

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

Within moments of his 2013 Wimbledon victory, making him the first British man to win that fabled competition in 77 years, Andy Murray gave a media interview that seemed almost as grueling as the match itself. When asked what had changed in the time since his heart-wrenching and emotional defeat on that same court the year before, Murray responded without hesitation. Out of breath and clearly exhausted, the new champion answered by saying that over the past twelve months he had: a) learned from his mistakes, b) worked extremely hard, and c) surrounded himself by a top-notch team.

I suspect that the very last thing on Andy Murray’s mind that July day was teaching the world about effective leadership, but that is exactly what he did. His tripartite prescription: learn from your mistakes, work hard, and surround yourself with a first-rate team is, in fact, a formula for all who strive to be successful leaders.

Learn From Your Mistakes

The best leaders are thoughtful leaders; they understand the benefit of quiet reflection as part of their work. The essential Jewish teaching of teshuva (repentance) suggests that each of us has the capacity for heshbon hanefesh (self-evaluation) and can learn from our errors. Judaism has never insisted that we are imprisoned by our past actions. Rather, our sources suggest that if we acknowledge our mistakes, we can move beyond them. Individuals who are too quick to overlook their failures, insisting that they are anomalous and have nothing of value to teach, or those who seek to blame others for their shortcomings, are incapable of effective leadership. Absent a willingness to deal head on with yesterday’s mistakes, to learn from them, and to improve, one cannot expect a different tomorrow.

Work Hard

The Talmud (Megillah 6b) says it best: “If a man says to you, I have labored and not found, do not believe him. If he says I have not labored but still have found, do not believe him. Only if he says, I have labored and I have found may you believe him.” What Andy Murray knew, and what effective leaders understand, is that there is no substitute for hard work. The privilege that often comes with power can be alluring. But no leader can succeed by sitting back and coasting or by phoning it in. No one is that good to be able to get by on natural talent or past performance alone. Leadership is difficult and painstaking. Defeat and setback come with the territory. No experienced leader hopes for instant results. Patience, tenacity and steadfastness are the necessary ingredients. Success will come but there are no magic bullets or quick fixes.

Surround Yourself with A Great Team

As Ram Charan and Larry Bossidy make clear in their work Execution, great leaders get things done through other people. The very idea of a stand-alone leader, without followers, is an absurdity. In the twenty first century, no single individual, however talented or brilliant, can know enough or do enough to succeed solo. Murray, on what was arguably ‘his’ day, was quick to acknowledge what the best leaders have always known: his success was not his alone. In the wonderful book, Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell argues that even the most accomplished individuals are the products of elaborate nexuses:

“… In order to understand the outlier I think you have to look around them—at their culture and community and family and generation. We’ve been looking at tall trees, and I think we should have been looking at the forest.”

In a Midrash (Tanhuma, Beshalach), God reminds the greatest Jewish leader, Moses, of the same thing. His success as a leader, God tells Moses, can only be explained in the context of his team – the Israelites who left Egypt. ”… In their merit I have elevated you, and because of them you will find … honor before Me.”

It is unlikely that any of us will play tennis like Andy Murray. But we who aspire to lead have much to learn from that 26-year-old Scotsman who in the aftermath of the biggest victory of his life offered a simple yet eloquent paean to the value of learning from our mistakes, working hard, and surrounding ourselves by a great team.

Leading diverse teams: worth the struggle

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

During a recent Chicago visit that included breakfast with students and alumni at Spertus Institute, newly elected University of Haifa President, Amos Shapira, was asked to reflect on a leadership lesson he learned in business that is pertinent for his new post in academe. Shapira, who formerly served as the Managing Director of El Al Airlines and of Cellcom Israel, Ltd., wasted no time in focusing on the value of building multicultural teams, which, he says, almost always outperform traditional ones. Among other things, this conviction has led Shapira and the university to emphasize coexistence between various sectors and strata of Israeli society.

Shapira is not alone in this assertion. Lori Brewer Collins of Artemis Leadership Group notes that multicultural teams trump their more conventional analogues “in the areas of innovating, understanding diverse markets, meeting customer needs, and aligning multiple organizational interests.”

The idea that teams are more effective when they are diverse has enormous resonance even for those who work in organizations lacking the conventional trappings of “multiculturalism.” Diversity exists in every enterprise and thoughtful leaders will seek to create teams that reflect those differences. Thus, one need not work in a global corporation with colleagues from around the world to reap the benefits of “multicultural” teams. What is needed above all else is a commitment to maximize the diversity that does exist within your organization. Gender balance, generational representation, and an array of skillsets, backgrounds, and perspectives will, if managed properly, enhance the likelihood of better decision-making and a richer, more creative work environment for all.

For much of our history, Jewish communities have embraced this message. The mishnah of Avot, for example, speaks of three crowns (ketarim in Hebrew) – a metaphor for a tripartite approach to communal leadership, in which power is shared among a diverse group of individuals and interests. The three crowns: Torah, Priesthood, and Sovereignty (often understood as metaphors for educational, religious, and political leadership paradigms) reflect differing perspectives that function best when they function in concert. In the aggregate such diversity enriches the depth and creativity of Jewish life. In healthy Jewish communities, from the biblical period to our own day, individuals from each “crown” come together to create a multi-faceted and richly textured Jewish experience.

As those who lead diverse teams will attest, however, the system of ketarim is not without its own challenges. By definition diversity is often difficult to manage. As Brewer Collins notes, such teams “can become expensive, unproductive hotbeds of frustration, low morale, and finger-pointing.” The very things that make diverse teams advantageous also make them high-risk. To be sure, divergent perspectives, differing sensibilities, and varying worldviews often result in the high levels of creativity and resourcefulness required to solve complex problems. But disparate points of view can also mean impassioned argumentation, protracted negotiations, and difficult conversations.

Those who lead diverse teams effectively do not minimize the significance of members’ differing perspectives. Nor would they deny that conflict is inevitable. To maximize the potential for creative solutions and innovative problem solving those differences must be celebrated and then harnessed. Successful leaders do not try to avoid friction rather they seek to manage it. With diversity come varied points of view, multiple approaches and even conflicting agendas. The job of the leader is to explore and exploit those differences while striving to find the best solution under the circumstances.

Too often we impose a binary approach to decision making – we force ourselves to choose between one of two options. We prefer quick decisions with a minimum of debate to a thoughtful exploration of multiple options. The effective leader avoids oversimplification and knows that making decisions too quickly is every bit as problematic as indecisiveness. Challenge yourself to reject facile choices and an “either-or” approach to difficult decision-making. Use the diversity that exists within your team to multiply options before making tough choices.

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

The humble leader

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

In the prior posting I referenced a recent visit to Spertus by the famed prognosticator, Nate Silver. Though it has now been several months since his appearance, I confess that I continue to think about what he said that day. One thing that stands out is his assertion that statisticians could increase the accuracy of their predictions if they were more humble. This called to mind a similar contention by a number of prominent leadership experts that humility enhances one’s ability to be a better leader and to make wiser decisions.

In many ways these seem counter-intuitive claims. While we all have doubts, what we want from our statisticians and our leaders is certainty. We want them to instill confidence; we need them to know what they are talking about. Anything that suggests tentativeness or hesitancy is off-putting and antithetical to the certitude we so desperately require. As Bertrand Russell once observed, “The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt.”

In much of Western culture and tradition, humility is associated with weakness; it is, if you will, perceived to be the embodiment of unleadership. And yet, it is precisely the willingness to acknowledge how little is known for certain that actually enhances one’s ability to make better decisions, whether in the C-Suite or the newsroom, the office or the community. Wise leaders understand the value of what is known as epistemological modesty, the willingness to say, “I am not sure” and “I do not know;” to acknowledge that even when we think we are right, we might be wrong.

In Jewish tradition humility has always been the signature of effective leadership. Moses was known simultaneously as the most humble of all men, and the most successful of all leaders. These are neither unrelated nor coincidental. All subsequent Jewish leaders are urged to emulate his example. Even the king, according to the medieval authority Maimonides, who powers were extensive, had to conduct himself in a fashion that was “marked by a spirit of great humility.”

What is it about humility that makes for better decision-making and wiser predictions? The famed teacher of leadership Peter Drucker reminded his students that the best decisions are made when we “bring our ignorance” to a problem, because most of what we think we know is wrong. Humility allows a leader to listen carefully to others, eliciting the views of people whose input might otherwise be ignored by one so confident as to believe he has all the answers. Arrogant leaders see no reason to ask difficult questions designed to uncover the truth, because they are sure they already know everything.

In their book Execution, business writers Larry Bossidy and Ram Charan offer their own paean to humility:

“The more you can contain your ego, the more realistic you are about your problems. You learn how to listen and admit that you don’t know all the answers. You exhibit the attitude that you can learn from anyone at any time. Your pride doesn’t get in the way of gathering the information you need to achieve the best results. It doesn’t keep you from sharing the credit that needs to be shared. Humility allows you to acknowledge your mistakes … It’s not a question of thinking less of yourself, it’s a question of thinking of yourself less.”

Thoughtful leaders are challenged to balance their own impassioned convictions and the confidence in their own judgments with an appreciation for genuine humility. That humility forces us to temper what we “know” with an acknowledgment that we may just be wrong. It reminds us that certainty left unchecked becomes arrogance. It closes us off to others and makes for poor decisions and bad leadership.

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

The importance of self-awareness

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

Students and colleagues often ask whether there is a sole attribute that defines effective leadership. Most experts would support the finding, encapsulated in a 2007 megastudy published in the Harvard Business Review, that there are no “universal characteristics, traits, skills, or styles,” that constitute the “profile of an ideal leader.” Good leadership assumes a multiplicity of forms, and it would be a mistake to reduce effective leadership to a single characteristic. That having been said, however, there is considerable evidence that without the trait of self-awareness, one cannot hope to lead effectively. As the widely respected Center for Creative Leadership explains, “… strong interpersonal skills, grounded in personal reflection and self-awareness, are the key to effective leadership.”

I was reminded of the importance of self-awareness recently during a presentation at Spertus by the acclaimed statistician, Nate Silver. In discussing why so many predictions fail, the man who famously foretold the results of the 2012 presidential election with astounding accuracy noted the following irony, “The more one acknowledges one’s biases, the less likely one is to make biased decisions.” To illustrate, Silver noted that individuals who admit to a bias in favor of hiring male candidates over similarly qualified female candidates, actually hire more women than those who claim no such bias.

This is a fascinating insight, and although Nate Silver was not talking about leadership per se, it has enormous resonance for those who lead. Simply stated, an important corrective in overcoming a prejudice is the self-awareness required to acknowledge that prejudice in the first place. Leaders honest enough to admit their biases are uniquely qualified to compensate for those weaknesses.

Jewish sources insist that though it is imprudent to deny one’s limitations, including predispositions and biases, the presence of those shortcomings ought not prevent us from leading effectively. According to the Torah, when God summons Moses to lead the Jewish people his reaction is to reject the call because of his own failing, averring “I am not a man of words” (Ex. 4:10). God then assures Moses that not only will He be with him, but his brother Aaron will serve as counselor and spokesperson. Only when Moses is certain that his weaknesses can be compensated for does he feel sufficiently confident to assume leadership of the people.

This is not the only episode in which Moses mistakenly supposes that a leader needs to be perfect, to know it all and to do it all. During the Israelites’ early years wandering the desert, Moses is called to task by his father-in-law, Jethro, for shouldering the entirety of the nation’s leadership responsibilities. “The thing you are doing is not right,” he tells Moses, ” You will surely wear yourself out, and these people as well. For the task is too heavy for you; you cannot do it alone” (Ex.18:17-18). Jethro goes on to instruct Moses to surround himself by capable individuals who can share in the leadership.

A similar idea is reflected in a now popular article published several years ago in the Harvard Business Review titled, “In Praise of the Incomplete Leader” (2.07). In it the authors make the following point, “No leader is perfect. The best ones don’t try to be – they concentrate on honing their strengths and find others who can make up for their limitations.”

Great leaders acknowledge their weaknesses. They take responsibility for their biases, but refuse to be defined by them. Thoughtful leaders learn to compensate for their limitations, sometimes by self-remediation, other times by surrounding themselves with people who bring to the enterprise talents, skillsets and perspectives that they lack.

Nate Silver’s insights challenge all who lead. Ask yourself: What are the biases that I bring to the table? In what ways do they impede my ability to lead effectively? What can I do to compensate for these limitations in ways that will enhance the overall leadership of the organization?

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

Revisiting a Joshua-esque Model of Leadership: Response to Rabbi Kenneth Brander

|

This article was originally published by eJewishPhilanthropy.com |

Cognizant of the well-known barb that in academe arguments are so passionate because the stakes are so small, I must nonetheless assert that if there are lessons to be learned about the value of collaboration from biblical personages then dismissing the example of Moses deprives us of a useful paradigm.

From its incipiency, Moses’ career as a leader was predicated upon a model of collaboration, in which complementary skill sets come together for the betterment of the people. Far from the blinding persona Brander tries to depict, Moses initially resists the call to leadership precisely because he feels ill equipped for the tasks at hand. Only when presented with a model of shared leadership in which his own abilities are augmented by divine assistance and the talents of his brother, Aaron, does Moses even begin to think of assuming responsibility for the nation (Exodus 6:28-30; 7:1-3).

Like many leaders, Moses struggled with the need to prove himself. But when confronted with the insights articulated by his father-in-law Jethro that all leaders are necessarily incomplete, and that no leader, however talented, can do it all (Exodus 18:13-23), Moses wisely reverses course and heeds his father-in-law’s advice (Exodus 18:24). Indeed, when he reaches the point of executing on his own, he goes even further. While Jethro’s instructions call for Moses to hand pick suitable individuals capable of assisting him, the first chapter of Deuteronomy describes that rather than do so himself, he eschews unilateral top down decision-making, and assigns the responsibility for selecting leaders directly to the polity. Thus, contra Brander, he empowers the people, creating a sense of collaboration and investment, rather than imposing his will nolens volens.

Rabbi Brander’s embrace of the “Joshua-esque model of leadership” ignores one of the most significant chapters in the history of his career, namely the episode involving Eldad and Medad (Numbers 11:25-29). When these two would-be leaders defy popular convention, and behave against type, it is Joshua, epitome of collaborative leadership according to Brander, who condemns their behavior and demands that Moses “restrain them.” Fortunately for those who treasure true collaboration in leadership, Moses is not persuaded by Joshua’s paranoia. “Are you wrought up on my account?” asks Moses. “Would that all the Lord’s people were prophets that the Lord put His spirit upon them.” It is Moses, not Joshua, who embodies a commitment to collaboration, recognizing that one size never fits all, that no single leader can succeed alone, and that the success of an enterprise requires a multiplicity of approaches and a diversity of leadership types. Collaboration is not cloning. As the great teacher of leadership Peter Drucker reminded his students, “Carbon copies are weak,” a lesson apparently lost on Joshua in this incident.

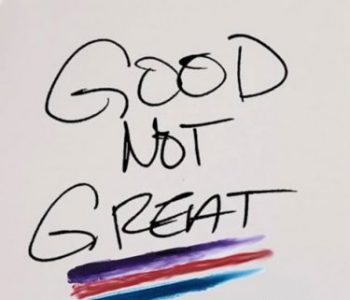

From Moses we learn something even more important about collaboration. Not coincidentally, the greatest Jewish leader of all time is, according to the Torah (Numbers 12:3), the most humble of all human beings. Indeed, Moses’ humility is pivotal to his success. Effective leaders know that collaboration begins with a willingness to check egos, to put the good of the enterprise above personal agendas. They acknowledge, as Bossidy and Charan make clear in their book Execution, that the best leaders get things done through other people. Long before Jim Collins lionized Level Five leaders whose humility makes the difference between good and great organizations, and long before Drucker coined the term knowledge workers to suggest that twenty-first century leaders are less likely to be specialists aspiring to know it all and do it all, and more likely to be coordinators of specialists, Moses underscored the critical link between collaboration and ego management.

Humility in a leader allows her to listen carefully to others, to admit his mistakes. A humble leader avoids haughtiness, learns from everyone regardless of place in the organizational chart. An imperious leader is unable to ask the questions necessary to uncover the truth because he is so sure he already has the answers. Arrogance prevents a leader from sharing the credit that is often seminal to the collaborative process.

Rabbi Brander speaks movingly of his wife’s efforts to collaborate with other mothers whose children faced the same fatal disease that tragically took their daughter. Her efforts provide stirring testimony to the lesson first embodied not by Joshua, but by Moses, that none of us is as smart as all of us. Whatever a Joshua-esque model of leadership might be, and with all due respect to the one whom Rashi describes as a pale imitation of his predecessor (Commentary on Numbers 27:20), humility in Jewish tradition is the Mosaic signature, and a model worth emulating for all who seek to embody a collaborative approach to leadership.

Dr. Hal M. Lewis is the President and Chief Executive Officer of Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership. A recognized expert on Jewish leadership, he has published widely in the scholarly and popular press. His books include Models and Meanings in the History of Jewish Leadership and From Sanctuary to Boardroom: A Jewish Approach to Leadership.

This article was originally published on eJewishPhilanthropy.com

Leadership: Better when we’re together

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

Several months ago, Marissa Mayer, CEO of Yahoo, generated considerable controversy with her decision to terminate the company’s long-standing policy allowing telecommuting or work from home (WFH). Though widely criticized by many as a “step backward for workplace flexibility,” I think there is much here (and in a similar move by Best Buy) that is worthy of consideration.

In explaining the policy shift, Mayer opined that people are “more collaborative and innovative when they’re together.” She is certainly not the first to come to this conclusion. The late tech guru Steve Jobs told his biographer that, “There’s a temptation in our networked age to think that ideas can be developed by email and iChat. That’s crazy. Creativity comes from spontaneous meetings from random discussions. You run into someone, you ask what they’re doing, you say ‘Wow,’ and soon you’re cooking up all sorts of ideas.”

A similar dynamic is known to be true in higher education, as well. Writing about online courses in the NY Times, essayist A J Jacobs noted technology’s limitations when he compared electronic discussions with traditional classroom engagements. Quoting the University of Virginia’s Peter Dewitz, Jacobs argued that online conversations deny “the rapid exchange of ideas that a true discussion would afford.” Speaking of his personal experience with online learning over the past year, Jacobs noted that “none of the interactions seemed as invigorating as late-night dorm-room discussions at my nonvirtual college in the late 1980s.”

[At my own institution, Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership, we have long favored a blended approach to Jewish learning. The not inconsiderable benefits that technology affords the learner must never supplant the similarly invaluable dynamic that takes place when students and faculty sit together in the same room to plumb the wonders and mysteries of a text face-to-face.]

In Judaism, for leadership to be effective it must be collaborative; power must be shared among and between individuals. Underlying many Jewish sources on leadership is a view that holds no single individual, however talented, can be effective by herself. When Moses seeks to shoulder sole responsibility for the Israelites after leaving Egypt, he is challenged by his father-in-law, Jethro. “You will certainly wear away, both you, and this people who are with you; for this thing is too heavy for you; you are not able to perform it yourself alone” (Ex.18:18). In a dramatic text found in the rabbinic literature, the sages criticize Moses, otherwise known as the most humble of all men, for trying to horde power rather than share it (Ex. Rabbah 2:7).

Leadership is about relationships, not about a single individual. Precisely because no one is capable of doing it all, organizations need to think seriously about how to best create an environment in which collaboration, creativity, and innovation can flourish.

Whether Marissa Mayer made the right decision or implemented it appropriately, I cannot say. But I do know that, in the words of Andres Spokoiny, President and CEO of the Jewish Funders Network, “innovation (and I would add creativity generally) rarely happens in a vacuum. It needs an ecosystem, a breeding ground that is conducive to the generation of ideas.” Such an environment requires more than technology. It demands the very conscious decision to put the right people around the table, and an affirmation of the truth that none of us is as smart as all of us.

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

Defining success

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

The business literature has been filled of late with innumerable discussions about success–how to achieve it, how to measure it, what it looks like, and where it comes from. Considerable controversy has emerged on this last point, in particular. Political junkies will remember an incident during the 2012 presidential campaign in which emotions ran high over who should get credit for the success of small business in America. Many took great exception to the suggestion that success is attributable to factors beyond the talents of an individual entrepreneur. Similarly, during a recent 60 Minutes interview Facebook COO, Sheryl Sandberg critiqued women in the workplace for attributing their success to “working hard, luck, and other people,” rather than to their “own core skills.”

Malcolm Gladwell, author of the 2008 book Outliers offered a different perspective on the roots of success when he observed, “We’ve been far too focused on the individual … in order to understand the outlier I think you have to look around them–at their culture and community and family and generation. We’ve been looking at tall trees, and I think we should have been looking at the forest.”

So which is it? When you think about your personal achievements do you attribute your success to your own core skills or to other people, luck, and outside circumstances?

Jewish sources offer a compelling perspective on these matters. Ours is a tradition steeped in principles of gratitude–to God and to others. Observant Jews endeavor to recite meah brahot at least one hundred blessings a day, expressing thanks for everything from the food we eat to our financial security. For Jews, public acknowledgment of our indebtedness is a prominent feature of every day and every festival. Arrogating to ourselves credit which belongs to God is a form of idolatry. But it is not just the Divine we acknowledge. We recognize our indebtedness to our politicos and our physicians, our parents, and our teachers, our students, and our colleagues. Even good fortune and luck are recognized as playing a part in human accomplishment. Crediting our success to others is not a sign of weakness. Acknowledging that our accomplishments are bigger than ourselves is a basic truth in Jewish writings.

The most successful Jewish leader of all times–Moses–is known, not coincidentally, as the most humble of all individuals. The sources tell us that his success depended upon a variety of external factors, both human–his brother Aaron, his father-in-law Jethro, the elders–and Divine. His prodigious achievements were neither compromised nor attenuated by his humility. On the contrary, his ability to give credit to others, to admit his shortcomings, and to collaborate, lie at the heart of his success.

What then is the relationship between personal skills and talents, on the one hand and outside factors, on the other? Jewish sources remind us that even humble leaders, those who readily acknowledge they owe their success to factors beyond themselves, need not deny their own achievements. Indeed, our classical texts caution against false humility, which must not become an excuse for timidity or indecisiveness. Even as they acknowledge their indebtedness to others, leaders must stand up for their beliefs. They cannot allow a false sense of humility to paralyze initiative or to weaken resolve.

This balance between self and others, between personal achievement and indebtedness to those around us, between humility and pride, is key to the management of our success now and in the future.

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

Leadership and authority

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

Political junkies will recall that in the midst of the recent sequestration controversy, President Obama took 12 Republican senators to dinner to discuss their differences. Almost without exception, every pundit and reporter, regardless of orientation, went out of his or her way to comment on the striking fact that, as a NY Times headline (March 5, 2013) put it, “Trying to Revive Talks, Obama Goes Around G.O.P. Leaders.” Indeed, the common theme in most of the press was that circumnavigation of the extant leadership was the only way to break the logjam.

Irrespective of politics, I must admit to being struck by a number of questions in this regard. To begin with, isn’t it leadership’s job to make things happen, to get things done? Why would one have to go around leaders in an effort to make the bold decisions necessary to serve the people who elected them? If others are capable of doing the job that the so-called leaders cannot, then who are the real leaders?

This entire episode embodies a dramatic example of how leadership and authority are easily conflated. Calling someone a leader because of their position or title is commonplace; we all do it. In his wonderful book Leadership Without Easy Answers, Ronald Heifetz of Harvard University notes, “In our everyday language, we often equate leadership with authority. We routinely call leaders those who achieve high positions of authority even though, on reflection, we readily acknowledge the frequent lack of leadership they provide…”

When we use the term leader without regard to the abilities, skillsets, behaviors, ethics, or vision of the individual(s) in question, we come to expect that our “leaders” are unable to lead. Thus, when we need to get something difficult accomplished we seek out those who, according to conventional parlance, are not leaders. This is particularly ironic since the willingness to take risks, make difficult and even unpopular decisions, and put those they serve above party or ideology, is the quintessence of leadership.

One’s ability to lead effectively can often be hampered by the very authority thought to lie at the heart of leadership. As Heifetz describes, “… the constraints of authority suggest that there may … be advantages to leading without it.” Thus in analyzing the sequestration dinner, two questions arise: What is it about the “leadership” that prevented them from leading? And, what is it about the 12 dinner guests that enabled them to lead even though they were not considered part of the leadership?

Political scientists have long known that, to paraphrase journalist Farid Zakaria, you’re a revolutionary until you acquire power and then you become a conservative. That is to say, once in a position of responsibility (not the same as leadership!), individuals often find themselves hamstrung and unable to manifest the courage required for effective leadership.

Many people mistakenly conclude that their ability to lead is enhanced by the acquisition of titles or elevated placement on the organizational ladder. While that is sometimes the case, it is not always. Indeed, in many instances the more authority, the less leadership.

As you reflect on your own work at the office, in the community, or elsewhere, consider how your ability to lead effectively is both enhanced and impeded by your rank or position. Let me know what you think.

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

What is Jewish leadership?

|

This article was originally published by JUF News |

When people learn that I am the President of an Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership, they often ask, “What is Jewish leadership? Does such a thing really exist?” To me, ‘Jewish leadership’ refers to the principles and tenets found in Jewish sources—classical and contemporary—honed and fine-tuned in Jewish communities over the millennia, which address such things as: the use and abuse of power, authority, effective decision making, collaboration, leadership ethics, succession planning, training, and the like. In my view, those who lead have much to learn from exploring these principles, whether or not they are Jewish, or whether they work in a Jewish organization, a corporate setting, or an entrepreneurial start-up.

Central to Judaism’s understanding of effective leadership is the matter of definition. The Hebrew word for leadership is manhigut. Like many Hebrew words, manhigut derives from a three-letter root, in this case n-h-g, meaning behavior. Simply stated, Jewish sources understand leadership as being about behavior. While it may not seem like much, I would argue that this linguistic insight provides a framework for answering some of the biggest leadership questions of our day:

- Where does leadership come from?

- What constitutes effective leadership?

- Who is eligible to lead?

- Are leaders bound to an ethical standard different from the rest of us?

- Can leaders be made (trained) or are they born to lead?

A worldview that defines leadership as behavior stands in sharp contrast to one that conflates leadership with rank or title or position. Similarly, linking leadership to behavior offers a different approach than one that equates leadership with wealth, physical attributes, personality traits, or gender.

Here’s an experiment you might want to run at home, at the office and in your community work as well. Consider the degree to which things would be different in your company or communal organization, or in the world-at-large, if leadership were defined as behavior. To that end, complete the following sentence: If leadership is about behavior, then …

When I try this exercise, reflecting on some of the major issues I observe on a regular basis, I note the following:

- If leadership is about behavior, then wealth, gender or age would not be defining criteria for those who lead.

- If leadership is about behavior, then organizations, including nonprofit groups, would invest heavily in training future leaders.

- If leadership is about behavior, then a leader’s ethics would be at least as important as her productivity.

- If leadership is about behavior, then risk-taking, change, and bold decision-making, not worship of consensus, fear of criticism, and the obsessive desire to be loved, would define leaders of our generation.

- If leadership is about behavior, then service to followers would be more important than blind loyalty to party or ideology.

While it would be a mistake to say that only Jewish sources hold this view, the Hebrew word manhigut articulates an approach to leadership that contrasts sharply with popular understandings of leadership, unfortunately even within the Jewish community. In the weeks ahead consider how leadership is defined in your organization. Do we use leadership to describe a person’s behavior or her place in the organizational chart? What specific behaviors do you associate with effective leadership? What happens when leadership is used to refer to something other than behavior?

—This piece originally posted in JUF News

Planning for Success(ion)

|

This article was originally published by eJewishPhilanthropy.com |

The time has come to abandon the insulting notion that programs of Jewish literacy, however excellent, are in and of themselves, leadership programs. Similarly, American Jewish groups must cease the dysfunctional practice of parachuting people into positions of communal responsibility just because they have been successful in business.

Thoughtful observers of the American Jewish scene cannot help but notice that over the past year considerable attention has been devoted in the Jewish media to the issue of succession planning in organizational life. Occasioned most immediately by the sudden departure of several high profile organizational CEOs, and fueled further by what some see as an increasing tendency to replace long serving executives with individual from outside the communal world, an electronic firestorm has erupted in the Jewish press.

Concern is hardly unwarranted. As far back as 2006 surveys have documented a looming crisis. A CompassPoint analysis in that year found that of 1900 nonprofit leaders, 75% planned to leave their job by 2011 (“Daring to Lead,” CompassPoint 2006). Even more dramatically, a study conducted for the Andrea and Charles Bronfman Philanthropies in 2009 predicted that, “within the next five to ten years, the baby boomers will retire and leave upwards of 75-90% of Jewish community agencies with the challenge of finding new executive leadership” (Austin and Salkowitz, “Executive Development & Succession Planning,” 2009).

The latest research from the Jewish Federations of North America corroborates these trends. JFNA indicates that during just the last 24 months, the rate of change at the CEO level in Jewish federations is approximately 27%, with many additional federations having initiated searches just since the start of the current fiscal year. At the large and large intermediate federations, the rate of change in CEO positions is fifty percent within the past three years.

Beyond the statistics, what is known for certain is that the organized Jewish community from synagogues to federations, from social service agencies to arts organizations is woefully unprepared to deal wit the coming realities. Six years ago, a DRG survey of nonprofit executives found that 58% of respondents indicated that neither the management team nor the board had ever discussed transition strategy (“Nonprofit CEO Survey,” 2006). And the situation has only gotten worse.

In his 2012 study of 440 Jewish organizational CEOs, Dr. Steven Noble identified two overarching themes that unfortunately seem to characterize most Jewish groups (“Effective CEO Transitioning…,” 2012).

- The vast majority of Jewish nonprofits (81%) do not have an emergency back up plan designed to address the unforeseen departure of a CEO (such as has been evidenced in recent months).

- An even larger percentage (91%) of those responding said that their organizations have no formalized succession plans.

The Jewish community’s failure to respond to these issues is not only bad business; it is antithetical to the best in Jewish wisdom and tradition. Woven throughout classical Jewish teachings and embodied in the example set by the quintessential Jewish leader, Moses, is a recognition of the fact that succession planning is the duty and obligation of all who claim to wear the mantle of leadership.

On the very day that Moses learns he will not live long enough to fulfill his life’s work and lead the Israelites into the Promised Land, he demanded of God that a successor be named. “Let the Lord, Source of the breath of all flesh, appoint someone over the community who shall go out before them and come in before them… so that the Lord’s community may not be like sheep that have no shepherd” (Numbers 27:15-17).

Here, Moses sets the standard for all those involved in Jewish communal life. Disappointed and scared as he surely must have been, Moses remained focused on the ultimate objective, getting the Israelites safely to the Land of Israel. To assure the continuity of the Jewish people, someone else would need to take over, and Moses understood that his job would not be complete unless and until he facilitated that transition. In the end, his own personal quest, however lofty or honorable, paled in comparison to the long term viability of the nation of’ Israel.

As if channeling Moses, leadership experts Jay Conger and David Nadler offer a strikingly similar assessment. “A truly successful legacy,” they counsel outgoing CEOs, “is one in which … successors flourish and company performance continues to be excellent” (“When CEOs Step Up To Fail,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2004).

Similarly, former Procter and Gamble CEO, A.G. Lafley reminds executives, “It’s not about you, the incumbent CEO. It’s about the institution and its future” (“The Art and Science of Finding the Right CEO,” Harvard Business Review, October 2011). Often times, taught Moses, the boldest act of effective leadership is preparing to pass the torch to the next generation.”

But long before a smooth transfer of power is possible, leaders must acknowledge one of the deep dark secrets of succession planning – the brutal fact, as Jim Collins calls it, that planning for succession is often painful and much easier said than done. The truth is that, for some, succession planning is an admission of mortality. For others, not withstanding the more than occasional headaches, power is alluring and tough to abandon. Leaders derive an enormous amount of tangible and psychic rewards from their work. The perks of power seem to conspire against the creation of a thoughtful approach to transitioning and succession planning. As the midrash states, “It is easy to go up to a dais difficult to come down” (Yalkut Va’etchanan 845). Having savored the limelight, long serving leaders are often reticent to make room for others, convincing themselves of their own irreplaceability. “All my life,” admitted Rabbi Joshua ben Quivsay in the Palestinian Talmud, “I would run away from office. Now that I have entered it, whoever comes to oust me I will come down upon him with this kettle [of boiling water]” (Palestinian Talmud Pesachim 6:1).

Further underscoring this point, the rabbis noted that even Moses had difficulty forsaking the mantle of leadership. In a remarkably insightful text, they suggested that despite his commitment to succession, when he realized he would no longer be in charge, Moses began to have second thoughts. “He can be compared,” said the sages, “to a governor who so long as he retained his office could be sure that whatever orders he gave, the king would confirm … But as soon as he retired and another was appointed in his place, he had in vain to ask the gate keeper to let him enter the palace (Deuteronomy Rabbah 2:5). Painful as it may be to admit, effective succession planning requires a recognition that careers and influence do not last forever.

And it is not just bald-faced ego that makes succession planning a challenge. The pervasiveness of “founders’ syndrome” haunts more than a few Jewish organizations. Long serving individuals, who have devoted incalculable amounts of energy, treasure, and self sacrifice over the years, often cannot face the prospect of handing over the reins. As Steven Noble found in his research on Jewish nonprofit executives, “many seemed to feel entitled to extend their tenures as long as they felt they were contributing.” Large numbers of Jewish organizational CEOs seemed to echo Louis XIV’s infamous pronouncement, “l’etat c’est moi,” manifesting what Noble describes as “a troubling degree of CEO expressed ‘ownership’ of their organizations” and a “high degree of personal possessiveness.”

Precisely because Jewish sources recognize that, in Conger and Nadler’s phrase, “succession is an emotional issue for many … and can lead to a variety of nonproductive behaviors,” the best of Jewish tradition insists that the training and development of the next generation be a preeminent communal priority. Which means that if organizational leaders continue to define succession planning as the singular process of replacing the CEO or even the board chair, they have missed the point. Succession planning is a systemic endeavor. It is an ongoing process that must inform and define the entirety of the enterprise. Key to effective transitioning is a system wide commitment to leadership training and development for both professionals and the laity across the organization.

An analysis conducted by Hewitt Associates called “Top Companies for Leaders,” first published in 2002, uncovered an incontrovertible link between financial success and great leadership training and development. The report notes: “organizations with a ready supply of talent and an ability to cultivate leadership capabilities up and down the ranks are well positioned to withstand turbulence in today’s business world… Said one company executive, “Leadership development is so much a part of our culture that we do not think of it as a discrete activity…” The report went on to find that “Companies such as GE, IBM, or P&G have a long tradition of CEOs and senior leaders spending a disproportionate amount of time on leadership and treating the development of the firm’s highest potential leaders as a personal responsibility” (Gandossy and Verman, “Building Leadership Capability To Drive Change,” Leader and Leader, Winter 2009). This is because, in the words of the great leadership teacher Tom Peters, at their core, “The best leaders don’t create followers, they create more leaders.”

To be sure, Jewish nonprofits characterized by tight budgets, small staffs, and the seemingly ubiquitous tendency that allows the urgent to trump the important, are not Fortune 500 companies. Nonetheless, if the organizational establishment is serious about addressing this crisis, it will begin to rethink its approach to the training and development of lay and professional leaders, without excuses. “Anyone who would exercise authority over a community in Israel,” teaches the Midrash, “without considering how to do so, is sure to fall and take his punishment from the hands of the community” (Song of Songs Rabbah 76:11,1). Or as the great expert on quality control, W. Edwards Deming used to say, “Training … is not mandatory, but neither is survival.”

For too long, and with very few exceptions, the organized Jewish community has made a mockery of leadership training and development, ignoring best practices from industry, the academy, and the best of Jewish tradition. Calling everyone who holds a titled position in the Jewish world a leader – regardless of skillsets or character does not make it so. So too, conflating volunteer orientation and donor education with leadership training only creates false and misleading expectations.